Teaching, Writing, and Research with AI

When Chat GPT first appeared in November 2022, the almost universal reaction in the humanities community could be summed up in one word – Yikes! Almost without warning this new tool seemed ready to make it incredibly easy for students to “write” essays using prompts that took no more than a minute to produce and then, if they were crafty, another 30 minutes to modify a bit so that it wasn’t quite so obvious that the essay had been written by a large language model (LLM).

I was about to give a take home exam in one of my undergraduate survey courses and decided I would ask Chat GPT to take the exam before I gave it to my students. When I read the responses the LLM gave me, I decided we would be doing the exam in class rather than as a take home, because I would have given a lightly edited version of those responses a B or B- grade.

Since 2022, we’ve watched as an AI arms race unfolded in our news feeds and for many teachers the sense of concern or even despair simply grew as the models have become better and better at writing. I’d like to propose that the problem is not the LLMs, but rather our response to what they are capable of.

My thinking on this subject has been heavily influenced by the work of Dr. Ethan Mollick at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. In his 2024 book Co-Intelligence: Living and Working With AI, Mollick argues that we need to accept that LLMs and other forms of AI are here to stay and so we need to figure out how to maximize their utility for what we do. To put it another way, how can LLMs help us be better teachers and our student be better learners?

Our work as history teachers and historians is generally divided into three domains: Teaching, Research, and Writing. Here are a few examples of how we might partner with the AI of our choice to upgrade what we are doing.

Teaching

One thing is for sure, we can’t keep assigning essays the way we always have. Our previous practice of giving students specific prompts just plays to the strengths of the LLMs. When a busy student can use Chat GPT or Claude.ai or Gemini to get a reasonable essay from one of our prompts, it should be no surprise to any of us that they do just that. But LLMs can do a lot more than just write history essays.

Instead of shaking my finger at my students and telling them they better not use an AI on their essay, I now tell them they must use an AI. I give them an essay prompt and tell them to write a three-page essay in response to that prompt. Then I tell them to give that same prompt to the AI of their choice and then they have to compare what they wrote with what the AI wrote and write up a one-page summary of what they learned from that comparison. Try this approach. I think you’ll be encouraged by what you read in those one-page summaries. My students see right away what they bring to the writing table that the AIs don’t. As one of them put it in her summary, “AI writing has no soul!”

Research

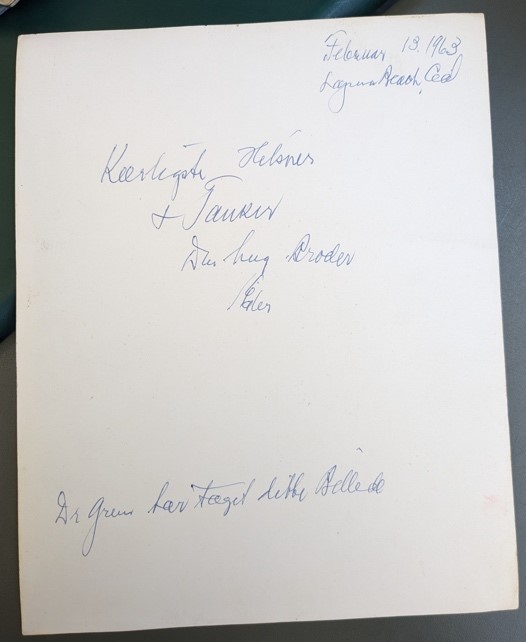

Increasingly, LLMs are becoming very useful tools for humanities researchers. I am currently working on a biography of a Danish-American immigrant. This past summer I was in Denmark for research and with the help of an MA student at the University of Aarhus I assembled a collection of more than 50 local news stories about this individual. I also met one of his descendants and gathered another two dozen or so letters and postcards he wrote home from the US.

All of that text was in Danish. I don’t speak Danish and I’m not going to learn it. But Chat GPT knows it and did an extraordinarily good job (I fact checked it with a native Danish speaker) translating all of that text to English, including some very difficult handwriting. What I especially appreciated was the way that Chat GPT offered up possible variations in its translation in case the most likely version wasn’t correct (it was).

Several of my colleagues here at RRCHNM have determined that Claude.ai is very good – when prompted properly – at reading handwritten data from 1920s-era census forms. This means they will be able to transcribe the data from these forms very rapidly. Claude does make mistakes, but so do humans, so the error checking they’ll have to do is not really any more than they would do with human transcribers.

Writing

The Danish immigrant who is the subject of the biography I’m working on was a vagabond. As I began thinking about how to structure the text, I asked all three of the most popular LLMs for suggestions on biographies of other famous (or obscure) vagabonds and they gave me a nice list of works to start with, much as I would have gotten had I asked a colleague. I then asked all three to tell me what the main themes in these works were and again I received some interesting lists.

None of this advice is dispositive, but it is a nice starting point for thinking about the life of the individual I’m working on. I would add that Chat GPT also pointed out that most literature on vagabonds has focused on men and so it offered up a list of female vagabonds as well that “you might want to consider.”

As a test, I gave all three LLMs the introduction and conclusion of my 2016 book Teaching History in the Digital Age, telling them that the text was from the final draft of a book. Could they offer suggestions for tightening my argument and improving my prose. I would have taken 85% of the suggestions offered. In future, I’ll be asking the LLM of my choice to review what I’ve written – not to write it for me – to get more of this sort of writing advice. I’ll also ask colleagues for similar feedback, but as we all know, colleagues are busy and it sometimes takes weeks or months to get their feedback. The LLMs got back to me in seconds.

All of these examples fall broadly into what Mollick describes as co-intelligence – combining my intelligence with the capabilities of LLMs to improve what I do. Speaking as someone who wrote his original college essays on a manual typewriter, I have never felt bad about using a word processor with a built-in spell checker. I’m not going to feel bad now about partnering with an LLM – as both a tool and as something that exists in a strange space between tool and colleague – to help me do what I do.