Evolution, Intelligent Design, Climate Change, and the Scholarly Ecosystem

March 2006

Scholarship

This essay was originally presented as the Keynote Speech at the Illinois Association of College and Research Libraries (IACRL) Biannual Meeting, Bloomington/Normal, IL, March 30, 2006.

The author’s version includes an audio recording of this keynote presentation, and may include updates.

I’d like to thank Dane and the organizing committee for the invitation to speak to you today. It’s a rare treat to be able to address such a large audience of engaged participants in scholarly communications.

Part of my job, as keynote speaker, is to be a little irreverant, a little amusing, a little thought-provoking, and a little context-setting. As the title of this talk suggests, I hope there’s enough of all of these to go around.

A couple of framing statements before I move into the body of the talk:

I’m a publisher, and I’m 48.5 years old. I’ve been in the publishing business since 1984, on the digital side of the book business that whole time, first as a typesetter (just as it was becoming computerized), then later as computer manager, and then as an electronic publisher, and now as director of the online presence of the National Academies Press.

I’m in this business because I love what we do—producing knowledge, expanding knowledge, promoting knowledge-based thinking, collecting and disseminating and enhancing and celebrating the work of the best minds of our culture. I stayed in the nonprofit sector during the dotcom boom period because I believe in what it does; I work where I work because it’s as close to an unalloyed good for humanity as I can find.

I love books. I love books so much, I’m laying out around $150/month to store the books I’ve gathered over my lifetime. I love the diverse craft of books—I notice paper quality, and typeface choices, and good kerning. I love the production, the process, and the reading of books.

I also like what books have done historically—spread perspective and knowledge far and wide. But I’m very aware that I’m watching the format I love—books—become an evolutionary backwash, not unlike an armadillo, or a crocodile. That is, something that evolved for a different age, yet which still has the ability to survive.

Finally, I want to warn you about something. For the most part, my predictive capacity has shown itself to be pretty good—if you look at my writings over the last 15–20 years, I’ve been generally accurate at predicting likely trends of the future. But I’ve made a few real lulus—for example, about 12 years ago, I predicted, to my later dismay, that the book would disappear in five years. I believed, at the time, that technology was marching so fast that we’d have digital readers, easy access to content, and would be walking around with e-books only, by 2000.

My fundamental error was in thinking that technology was the driver, rather than the human culture using the new technologies.

I teach a course on electronic publishing for George Washington University’s “master’s in publishing” program, and because my most recent class had 24-year olds through 55-year-olds, we got to explore in some detail the differences the generations had in their relationship to their online world. Those under 30 had grown up with the computer, and had a different set of fundamental assumptions about the digital world.

I now believe that the book will remain a marketable, if declining, commodity for another decade, because there are so many of us who love books—but that for the 30somethings, the social applications of technology will change their scholarship, their research, and their teaching.

So I won’t be talking today about particular technologies, or Google’s Print Library, or institutional digital repositories, or XML or PDF or JPG or HTML. Rather, I want to address the larger strategic problem that we, publishers and librarians, are facing, and how we might respond to it.

Cathy Davidson, a dean at Duke University, in remarks on humanities publishing for the ACLS, entitled “Crises and Opportunities: The Futures of Scholarly Publishing,” writes one of the best listings of some of the issues facing the current system:

“The problem is that we have tied tenure to the publication of a scholarly book. No, others say: uncoupling tenure from books cannot solve the problem because journals are in trouble, too. Others suggest that the problem is the scholarly monograph itself, or that the problem is curtailed library spending on humanities books. The problem is price-gauging by commercial publishers of science journals, necessitating that libraries spend less money on humanities and social science publications. The problem is chain bookstores, the dwindling number of independent bookstores, and the increasing conservatism of those that remain. The problem is electronic booksellers like Amazon.com with their heavy discounting and selling of used books. The problem is that books cost too much to produce. The problem is that electronic publishing is too expensive and doesn’t work for monographs. The problem is shrinking subsidies to presses in the wake of cutbacks to higher education for state universities…..

… [ more problems] …

The problem is that, since 9/11, people are watching CNN and not buying books, trade or academic. The problem is that university press books are underpriced relative to their production costs. The problem is that university press books cost too much relative to the income of their target audience. The problem is too many books. The problem is too few books. The problem is too many books of one kind and too few of another. The problem is students don’t know how to read any more.”

She concludes, “The problem is that almost all of the above are part of the problem. Fixating on parts means that we never arrive at an overarching solution.”

That’s the best distillation of the problems as currently treated, and it’s quite daunting, especially in the humanities and social sciences. But there is a key element missing from this analysis, for nearly all disciplines, and that’s what I want to address today.

This talk is an extended metaphor about the gardens we have built, the ecosystem we inhabit, and how it is being influenced by the climate change of the Internet. It’s about evolution and about abundance.

This extended metaphor helps explain the strange new digital world we inhabit, and has helped me, I think, make better decisions about the trends I see in that world.

Evolution

Evolution is a remarkable thing. My father was an evolutionary biologist, a psychologist, and an animal behaviorist, and so I grew up with evolution at the dinner table. We didn’t say grace; we talked about the evolutionary bases for the development of pairbonding; of teenage risk-taking as innate behavior with evolutionary, but not individual, advantage; of innate fight-or-flight responses to threats. Evolution is in my blood, much like Genesis is in the blood of those raised on a daily dose of the Bible.

Evolution is not survival of the strongest, or failure of the weakest.

Evolution is not fair; it’s not predictable; it’s not kind. Nor is it cruel, or chaotic, or unfair, for that matter. It’s what happens when environmental pressures change.

In a stable ecosystem, evolution happens within that environment very slowly, if at all. There are few if any advantages that accrue to any unusual genetic fluke, so there is no unusual likelihood of those genes being disproportionately represented in the next generation of a species’ offspring. In an ecosystem with no pressures, little changes.

In island ecosystems—say, the Galapagos—as populations increase, there are pressures to find new niches (as shown by crossbill finches), where new food supplies can be taken advantage of.

Natural genetic variability will lead to some gradual changes, but nothing causes dramatic variability like dramatic changes in pressures. Pressures where a high proportion of a species die, leaving the more adaptable or more genetically extreme to reproduce disproportionately. Countless subspecies go extinct because they happened to be born to parents whose genetic differences were disadvantageous.

Evolutionary pressures are driven by the carrying capacity of an ecosystem. Population density, resource availability, climate variability, and any number of environmental factors and ecosystem dependencies can affect the carrying capacity of an ecosystem for any species.

Start changing a primary characteristic of the ecosystem—say the weather—and great evolutionary changes begin to happen. In that case, genetic diversity in a species can become a strength. That extra-hairy mammal has a better chance of surviving a cold snap, and therefore a better chance of passing on her genes, and therefore a better chance that five generations later that species has a more hairy population. Or that one insect’s slightly better ability to dry off, after a heavy rain, means he has a slightly better chance of avoiding predators, and so is slightly more likely to pass on its genes.

Over the next 40 minutes I’m going to extend the ecosystem metaphor—and that of intelligent design and evolution—into the world of scholarly communication and publishing. I want to address what I’ve been concluding recently about the pressures on the scholarly ecosystem. Part of it is pretty scary for you and for me. Part of it is really exciting.

Our scholarly ecosystem is being fundamentally altered by population shifts, by resource availability, and by the huge environmental shifts happening because of the winds of climate change: the Internet and the interconnected world.

The National Academies Press

At the National Academies Press, we’ve been trying to prepare for these shifts, and so before I develop this metaphor further, I need to spend a few minutes giving you an overview of what we’ve been doing at the National Academies Press for the last 12 years—and especially over the last seven—as we have tried consciously to evolve.

The NAP publishes the reports of of the National Academies: the National Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Medicine, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Academies’ operational arm, the National Research Council. Our publications are mostly analyses of the current state of a science, generally requested by government, intended to inform policy decisions.

We are an independent, prestigious, non-governmental organization that functions as “advisor to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine.” Report topics range about as widely as you can get: Are polygraphs dependable? Should iodotrifluoromethane be regulated as toxic? what’s the quality of cancer care in the US? is our food distribution system susceptible to terrorism? what are the trends in Arctic geoscience?

The NAP is unusual—a genetic outlier, if you like—in that while we are a University-press-like publisher, we are very closely allied with our institution. Even odder for a modern university press, our institution is our author base.

As the publisher for this organization, we’ve been given a peculiar mandate by our institution: to maximize dissemination, while remaining completely self-sustaining.

This is our paradox. We are expected to give away as much as humanly possible, while still selling enough books to survive financially. To do this, we chose to develop our own Web systems, presentation architecture, and infrastructure—partly because we are this kind of mutant form of publisher. Our paradoxical mission drives most of our choices. For us, robust Digital Rights Management hardly makes sense. For us, the standard industry mode of raising the economic value of a book—access restriction—doesn’t make sense either. Nor does it make sense to provide full free access to all PDFs to everyone, at least at this juncture.

Instead, we built a page-navigation and online browsing system that strives to find the right balance between utility for the reader, and encouragement for some readers to purchase the book.

- Openbook Page, every report page displayed with navigation, search, purchase options

- Active Skim View of every chapter, to ease online browsing

- Web Search Builder, a means of using the key terms of any chapter to build targeted searches of Google, Yahoo, MSN, as well as the National Academies Press

- Reference Finder, a Web form into which one can drop a rough draft or an article to “find more like” it, or build searches from it

For our primary audience—who tend to be what I call “knowledge wonks”—these tools can be put to use effectively. For the casual reader, they can be useful, if a bit odd.

I think the NAP was forced, a bit earlier than most, into adapting to the climate change of the Internet. We’re in the sciences, and our audiences were early adopters. But most importantly, we have a parent institution for whom knowledge dissemination is a prerequisite for fulfilling its primary mission.

NAP began its tentative steps toward open access back in 1994. This was before my time at the Press, and I have to admit that when I first saw their free online page images, I thought they were crazy. Who would buy a book if they could read it online for free? At the time, one had to go from page i, to ii, to iii…, there was no searching, and no chapter navigation. Yet that model’s success forced me to rethink some of my ideas.

Around that same time, I was helping build Project Muse, the Johns Hopkins University Press online journals project, which most of you probably subscribe to. Even early on, I watched the more open access Muse journals like PostModern Culture get far more traffic than the closed ones. It was at Project Muse that I did a back-of-the-envelope calculation which convinced me that we were spending more of our grant money preventing people from access to the online journals, via security and IP-range subscription system development, than we spent enhancing access and adding value. This opened my eyes to some strange realities of electronic scholarly publishing.

So I greeted with open arms the opportunity, in 1998, to take on the NAP paradox, and to help develop an open access model that would be appropriate for the dual missions of the Press. We were institutionally encouraged to try to find new ways of using the Internet for publishing, and so we added fulltext searching in 1998, improved navigation in 1999, began replacing page images with HTML text in 2000 and 2001—all to make it gradually more open. My boss Barbara Kline Pope, the Director of the Press, supported these risky steps, knowing that, at worst, we could always pull back if we started to suddenly lose tons of sales.

In 2002, after we were already the most open book publisher on the planet, Bruce Alberts, President of the National Academy of Sciences, and the Academies’ boss of bosses, gave me the most amazing marching order:

“Michael,” he said, “take more risks.”

Amazing, since we thought we were already risking a lot!

But more to the metaphoric point, Dr. Alberts is a biologist, and evolution is in his blood. Risks are key to evolutionary success in a changing world. Staying the same—being a monocrop like genetically identical corn, for example—is a recipe for species extinction.

This corn is genetically identical. Every ear grown is at the same height, maximizing efficiency for combines and agribusiness. But a year-long cold snap, or a new kind of corn rust, could easily wipe out 100% of this monocrop corn.

With a crop with genetic variability, however—including “risky” genetic behavior—perhaps only 95% of the corn would die. But the corn you would harvest and hopefully plant the next year would be resistant to whatever killed the rest. This corn would be more difficult to harvest, less “efficient” as agriculture, but it would survive.

So the NAP has tried a variety of risky things over the last few years—things like the Active Skim, and Web Search Builder; like providing free PDFs for many of our publications, trying to strike the right balance of openness, while encouraging sales of books to individual visitors.

Because we were early mutants, we recognized the Webby future earlier than many organizations. Consequently we made conscious choices to take advantage of the new opportunities.

For example, we built our pages explicitly to be juicy to search engines.

We wanted to be “in on the ground floor” of search engines—because the earlier you’re deeply in there, the more likely you’ll be able to capitalize on the compound interest of a Web-connected world of participants—they’ll find you, and link to you, and that will raise your visibility and your search rank. We built specifically to have permanent pages that could be easily linked-to by URL copy/paste—this long before blogs, and permalinks. And we built specifically to encourage exploration of the breadth of our material.

Most of our Web choices and strategies were designed with the “wild Web” in mind. We knew that the normal distribution patterns—wholesalers, library distributors, bookstores, and the like—were, or would be, already pretty well handled, and that data (and content) would flow through its normal channels. For us, the Web was a new domain, a new ecosystem with different abundancies, and thus different survival strategies.

So far, so good—we get 1.25 million visitors per month. The average user browses around 10 book pages and 5 other pages—an astonishing rate for the Web. And though we’ve begun to plateau on sales over the last year, it’s still at a sustainable level. NAP’s website brings in 25% of its overall revenue, and 40% of its annual orders. We sell PDFs on about half our books, and give away PDFs for the rest. We provide FREE access to all PDFs to 167 developing countries, yet still give away hundreds of millions of book pages every year.

Intelligent Designers

Thus far I’ve touched on scholarly communications, evolution, ecosystems, carrying capacity, and other themes. I’ve also touched on the mutant publisher called the National Academies Press, a genetic outlier that has managed to take advantage of new niches in the ecosystem because of its peculiar genetic makeup.

Now let me take you into the surprising part of this talk: Intelligent Design. For many of us, that term means creationism. In this context, however, it’s more about conscious choices, about selective inclusion, about being the demigods who have constructed and maintained a beautiful garden.

You and I—that is, academic librarians and scholarly publishers—have been intelligent designers of the scholarly communications ecosystem for the last century.

Publishers and librarians both strive to impose order on the multiple flowerings of academe. We both endeavor to enhance access and readability, both seek to improve the comprehensibility and the organization of those works, we both labor to enable the works of the finest minds of our cultures to enrich the minds of the next generation of learned thinkers.

Historically, scholarly publishers and libraries have been the epicenter of communication. We were both vital for centralization, validation, production, and dissemination.

Publishers were essential, being the pre-filters of relevance, mining gold from the ore of submission piles, or of annual meeting presentations. Publishers who polished the prose, making those brilliant original minds more comprehensible; who found readers and markets, and who gambled a year’s salary on publishing a book, to ensure it was the best possible product. We published only the best we could locate, and then filtered out what was too specialized, too outlandish, or too unfocused.

Librarians were essential, being those who centralized the marketplace of ideas, who organized and catalogued and invented finding aids for the vast diversity of content. Librarians were also the selectors, the filters, the discerners, driven by the necessities of time, space, and budget. You were not omnivorous, or complete—rare is the archive of really bad paperback novels from the 50s and 60s. More rare still is the vanity press publication archive, or the two-books-and-out publishers’ archive, those who tried to become a publisher but never understood distribution chains and markets enough to get their books out in the world. Given limited budgets, these kinds of books were unlikely to be of appropriate value to the library, or to the university, and so were weeded out.

That synergy between publishers and librarians created what I think of as “an ecosystem of quality.” All the material, in any library, had been vetted several times over—by the acquiring editors, by peer reviewers, and by collection developers. If you went into a library (or a publisher’s catalog), any reader could pretty much be certain that any book pulled from the stacks was worthwhile in some way.

The visuals I’m using for this period are the manicured gardens of estates, and the careful beauty of the National Arboretum. These are crafted ecologies, and their beauty and value shouldn’t be minimized. We garden to be sure there are no weeds; we fertilize the works of the authors; we tend to the flowerbeds of academic disciplines.

But as intelligent designers of these ecologies, we are at peril of becoming moot—especially because we’ve entered an era of tremendous evolutionary change brought on by the climate change of the Internet.

Climate Change

That climate change is creeping slowly over our controlled environments.

New, alien species have begun to run riot without natural predators. Fewer bees may be pollinating our flowers. Trees that could handle cold now have to handle heat.

Worst of all, for the garden’s potential visitors, there’s often more interesting flora and fauna Out There.

Out There, in the wild; Out There, where there’s so much biodiversity. Out There, where it’s not necessarily vetted or peer reviewed or validated, but it’s really, really interesting.

I have long believed that any time spent on interesting stuff, is time well invested. These days, I find that there is a functionally infinite amount of interesting stuff, Out There in the wilds of the Internet.

The amount of material I can find from my chair—without going to a library, and for free—is endlessly interesting, for any purpose I can name. Worse for us “intelligent designers,” it is generally sufficient to answer my question or give me perspective. I don’t need centralization of resources, I need resources I can access that are well indexed by Google or Yahoo. The raw convenience of time, plus the endless fascination of endless content, means I don’t take advantage of the library’s distilled, controlled, high-quality collection.

This is the resource pressure of abundancy driving evolutionary change in our ecosystem—our customers have not only distractions, but legitimate alternatives.

The New Ecosystem

In the New Ecosystem, a wide variety of formal material is available as Open Access, and this is what tends to be increasingly read, and cited, and linked-to.

In the New Ecosystem, plenty of legitimate authors can make legitimate content available for free, to anyone with a Web connection. In the New Ecosystem, usefulness and ease-of-use are the necessary calling cards. Quality and dependability, while perhaps appreciated, can still be overwhelmed by that abundance.

Economics of Attention

Information itself had a slower pace ten years ago. Thirty years ago it was dramatically slower. For good or ill, we are now an impatient people with seemingly infinite, instant resources. We pay now with our time, as much as our wallet, in the Attention Economy.Attention is shifting, I’m afraid. That’s part of the climate change metaphor—I’m afraid the glaciers are melting, and the ocean is rising, as attention is shifting away from our beautiful gardens.

Today, if something’s not available digitally, it’s rapidly becoming as good as invisible.

That’s the worst fate possible for a scholar, or for any meaningful content —to be invisible.

Attention is the currency—even the food supply—of the New Ecosystem, and librarians and publishers can’t participate if we’re locked down and self-barred from participation.

We are moving into an age of participatory online culture, which is a dramatic change in the weather. If publisher and library resources aren’t available to that population, we may not be considered part of that culture. Bluntly, if something is locked away, then the integrating systems of search engines can’t index it, fewer people can quote from it, and nobody can link to it.

Web 2.0, the Web as a platform

Tim O’Reilly, a publisher and Internet luminary, has written eloquently about the some of the changes going on in the developing information ecosystem. One of his now overused and overhyped memes is that of “Web 2.0″—the idea that the Web has reached a level of ubiquity and dependability that businesses can find new models, using the Web itself as a platform upon which to build.

These are businesses which could not exist without the Web. The “participatory culture” I mentioned a moment ago is essential to these new kinds of businesses.

There are 30 million blogs that people update more than once per month. Vox populi indeed.

From Technorati.com, as of March 11: “The Pew Internet study estimates that about 11%, or about 50 million, of Internet users are regular blog readers. According to Technorati data, there are about 70,000 new blogs a day. Bloggers—people who write weblogs—update their weblogs regularly; there are about 700,000 posts daily, or about 29,100 blog updates an hour.”

From Flickr.com: On February 15th, the 100,000,000th photo was uploaded—each photo tagged in some way, and available for free browsing. Flickr depends on the engagement of people—people willing to spend a moment entering some descriptive words about the content of a photo. There is no controlled vocabulary, no official taxonomy, no authority files—this is the iconic example of the term “folksonomies.”

These and other “social networking”-driven sites demonstrate a different information model than we are accustomed to seeing.

Do I need to even mention that Encyclopedia Britannica was first published in 1771, while Wikipedia is just over 5 years old, and yet a recent study found them of similar accuracy?

Myspace is free and used by 65 million people, and is used intensely and daily.

Craigslist makes classified ads useful and free, nation- and world-wide, has millions of users, and has a total of 1.75 fulltime employees.

Boingboing.net, a blog “directory of interesting things,” produced by a group of 5 unpaid “interesting people” and no staff, gets more traffic than CNN.com.

Google Video and Yahoo Video and dozens of other video repositories mean anyone can provide fast, free downloads of their material.

I can—and have—spent hours reading and watching fascinating stuff produced by some guy in Toledo, or Fresno, or Tuskaloosa.

In terms of the Attention Economy, that means that for those hours, I was not watching television, I wasn’t reading a book I purchased, I wasn’t reading a journal I bought access to—I was watching a participatory culture’s creations via the platform of the Web.

Here’s a selection from Tim’s O’Reilly’s list of key elements and lessons learned about the “Web 2.0 world”:

- Services, not packaged software, with cost-effective scalability

- Control over unique, hard-to-recreate data sources that get richer as more people use them

- Trusting users as co-developers

- Harnessing collective intelligence

- Leveraging the long tail through customer self-service

- Lightweight user interfaces, development models, AND business models

Tim’s focus is mostly on the business end, but some of these lessons have real significance to the questions I’m addressing here. How can we “trust users as co-developers?” How can we integrate user interaction to help content “get richer as more people use them”?

They are also in some ways antithetical to our traditional “intelligently designed garden” model. “services, not products”? “customer self-service”? “Trust users as co-developers”? How do those approaches fit into the current model of publisher or librarian? It’s not part of our DNA, but it may need to be.

Scholarly Communications

I recently had a conversation with the new head of the Social Science Research Center, which has heretofore worked with university presses to publish a handful of booklength works every year. They are in the process of shifting to a Web-driven model, with print as simply an artifact, not the culmination. They recognize that for their audience, Google and other search engines are the primary centralizers now, not the publishers or even the libraries. They need to be able to be nimble, quick to respond to key issues, and be able to publish smaller works that may not have a print market—so they’ll take publishing “in house,” use Lightning Source to print on demand, and publish mostly for the Wild Web “Out There,” consciously engaging their audience as participants.

The Web 2.0 realities of participatory engagement may be perfect for scholarly communities—apart from the issues of tenure and accreditation—in that the number of, say, Latin American History scholars is small, but they care a great deal about the topic, and will engage directly with the content. Their need for a participatory community may outweigh some of the benefits of traditional publication—or may simply be considered a different form of publication.

I anticipate—and even hope to help develop—new Web-based mechanisms for group collections and tagging of distributed scholarly resources online. But especially with those tools, if material isn’t available online, it may gradually disappear from the immediate consciousness of those scholars—as I think is beginning to happen already.

The Scholarly Ecosystem

In 1993, I tried to outline for a Harvard/MIT Workshop on Scholarly Communications and Intellectual Property what I thought was likely in the coming Internet era. What I saw, and what I didn’t see, is I think illuminative. On the one hand, I foresaw many of the financial, intellectual-property arrangements between various entities—the new businesses that were started by the intellectual property industry. What I didn’t see was what the loss of centralization would mean, and what the rise of the participatory culture would mean.

The “intelligently designed” garden ecosystem for scholarly communications includes serious adherence to copyright law; includes nonprofit and for-profit commercial enterprises that physically centralize certain skill sets; presumes a centralization of resources in libraries and on campuses. It presumes the book is the culmination, where ideas are fully explored. It presumes a kind of research that is measured, and thorough, and relatively conclusive. It also presumes that all information has value.

The historical reasons for the co-evolution of these parts of the existing ecosystem are perfectly clear: production as well as collection had to be centralized to be efficient, and even still was quite expensive; distribution mechanisms were all physical, travel was expensive, and it was cheaper to distribute ideas through paper than to do it physically, apart from annual meetings of specialists—again, centralizing physical atoms.

The New Ecosystem for scholarly communications is becoming very different because the niches mandated by physicality are in decline. This is the climate change in specific—the change from physical weather to digital weather. Copyright law is just a nuisance and a barrier in the New Ecosystem, and Digital Rights Management technologies won’t solve it, because they’re also a nuisance. In fact, a solid argument can be made that mindless adherence to the principle of monetizing the value of content by restricting access may be counterproductive as an evolutionary strategy.

w Ecosystem, the physical centralization of editorial offices may be less necessary, and the network will enable ever more “virtual collaboratories” for scholarly development. These need not be 501(c)3 organizations—they may be transitory, or Association-based, more like subcommittees of participants.

Centralization of physical resources becomes much less important in the New Ecosystem—though centralization of virtual resources is still vital.

The New Ecosystem does not presume that the book is the culmination of scholarly research. The culmination project in the new ecology may be something entirely different—which might have as many words as a book, but is likely have broader diversity, an active index, hypertextual navigation, more examples, and the possibility of external users tagging, commenting, and participating in the project. Perhaps most important, great gobs of it will not stay static. Instead, it may be a constantly evolving project, with material added, modified, deleted.

Finally, the New Ecosystem does not presume that all information has financial value. In the old model, it was a precondition. Nearly every word published had a price on it. In the new model, information forms and types are able to find their appropriate requirement for capital. And scholarly communications have a much higher social value than financial value—so it may be that the economics of the existing ecosystem are actually relatively antithetical to the natural communicative balance between scholars, their peers, and their audiences.

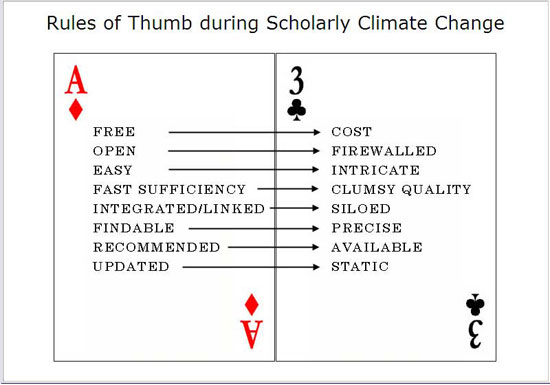

These are the ecosystem realities that seem to have developed over the last few years, for content online:

Results of Scholarly Ecosystem Climate Change:

-

- free trumps cost

- open trumps firewalled

- easy trumps intricate

- fast sufficiency trumps clumsy quality

- integrated/linked trumps siloed

- findable trumps precise

- recommended trumps available

- updatable trumps static

Climate Change Speed

We tend to think of climate change as gradual—weather patterns becoming one degree warmer, a bit drier over time, etc. We want to believe that, because anything else seems too scary. However, there’s plenty of evidence that climate change can occur with startling rapidity. And certainly human society, with new technologies, has been shown to change really fast.

In a 2002 report from the National Research Council, called “Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises,” a fairly frightening case is made that the available evidence indicates that dramatic climate change has occurred with remarkable speed.

From page 1: Recent scientific evidence shows that major and widespread climate changes have occurred with startling speed. For example, roughly half the north Atlantic warming since the last ice age was achieved in only a decade, and it was accompanied by significant climatic changes across most of the globe.

From page 1–2: The new paradigm of an abruptly changing climatic system has been well established by research over the last decade, but this new thinking is little known and scarcely appreciated in the wider community of natural and social scientists and policy-makers. At present, there is no plan for improving our understanding of the issue, no research priorities have been identified, and no policy-making body is addressing the many concerns raised by the potential for abrupt climate change.

This picture indicates that in as little as three years, dramatic transformations can take place.

I’ve made predictions before, and while I’ve been flat wrong a couple of times, I’ve mostly been pretty accurate about trends like those that I’m calling the climate change of digital information.

And my prediction is this: we have around five years to adapt, and another five years to adapt further. Books will have an audience for at least that long, and longer. But scholarly publishing and scholarly communications will be changing very quickly during that time, and many of us may not weather the change well.

What’s to be done?

The work we do is noble work, and is needed—that work of identifying, enhancing, collecting, qualifying, providing access to the highest quality content. But the way we do that work will have to change. Unfortunately it may have to be dramatic change, if we are to retain relevance in the New Ecosystem.Libraries have historically been a place people go TO, rather than organizations who do outreach and marketing and engagement with the campuses. University presses have been identifiers and publishers of books, and haven’t provided services to their institutions in decades. And I suspect both of those have to change, dramatically.

What we do is important, but the importance of our work will not mean we will prosper in the Attention Economy. Just because we’ve always been central, doesn’t mean we will continue to be, in the new participatory ecosystem.

What can libraries and university presses do?

-

-

- Prove our value in the New Ecosystem by adapting to changes

- Find new niches that take advantage of our existing strengths

- Engage with our institutions, and with our faculty and staff. They are the customer base, your “market of one.”

- Work with your counterparts. Publishers have skills that librarians don’t have, and vice versa. Both share understandings that can benefit the institution

- Develop specialized skills: on-demand research assistance, using the trained imaginations of libarians, and using specialized tools for both Web and closed-source resources

- Develop Web brand recognition—internally and externally

- Develop an academy-wide, 21st century “seal of approval” for Web resources.

- Make content more openly available. This means publishers, libraries, special collections

- Work with search engines and scholarly societies

-

One semi-outlandish model of participation might be via a scholarly-publishing “tagging” approach for Web resources, with a central taxonomy, as a means for librarians to actively participate in the emerging Web intellectual ecosystems. Actively explore the web to identify material meeting research library standards. Perhaps not “catalogue the Web” but perhaps “catalogue the best of the Web.”

Right now we are leaving so much of this to others, like Yahoo and Google and Flickr and the commercial sector. Why are we doing that? This is our space—the knowledge universe—and I’ve yet to see a concerted, coordinated effort from librarians to help guide the developing information universe. And I wish you would.

I’m saying this sort of thing to publisher communities too. Scholarly publishers must learn to be driven less by fear and more by opportunity; we must have the institutional support to explore new models that risk existing cost-recovery models.

What I’m saying is that publishers and librarians need to do what they are most averse to doing:

Take More Risks

Let me go back to one of those dinnertime conversation with my father and family, about evolution:

Teenage boys are the greatest risk-takers across the primate species—even across mammals in general. It’s sensible, from an evolutionary sense—young males are the most dispensable, in terms of maintaining reproduction. But if the risky behavior (in eating different foods, going farther afield, or leaping even farther across trees) ends up opening up a new environmental niche, then those genes may prosper. The older generation tends to take fewer risks.

Scholarly publishers and librarians are primary actors in a very mature, stable ecosystem that evolved within the constraints of the physical world, and developed to maximize species stability within those environmental constraints.

The Open Web world is the gangly, risk-taking teenager in comparison. The participatory-culture folks are all taking risks, going out into a new territory—and what they are discovering and creating is a huge, self-defining, complex, informationally rich ecosystem, as satisfying, to them, as what we built was, to us.

Bluntly, in the new scholarly ecosystem, we have to do a lot more risk-taking than we currently are. We have to recognize that our roles in the New Ecosystem will be different, and that our job descriptions will change even if the missions don’t.

Our missions must be to help build trusted, well-crafted content for our institutions and for our audiences, and to be agile while doing it, regardless of our historic habits. That is, we must be both stable and fleet of foot. Another behavioral paradox, not unlike the NAP paradox of making our content maximally open while still remaining financially sustainable.

Climate change can happen abruptly, as I’ve said, and its ecological repercussions can also happen rapidly, for particular species. We are entering a complex, New Ecosystem, and it will keep on creating evolutionary pressures for the foreseeable future. Our publishing and library imperatives, our organizational and business models, our underlying funding streams, and our status-conferring confirmations, all of these will be changing, relatively continuously. This kind of change is something we have no history doing, but which we’d better learn how to do—and do as partners. Be proactive, not reactive.

Scholarly publishers and librarians are interdependent species, and so as we move into this new participatory culture, we have to actively work together to stay read, and to stay relevant. Risk is a tough thing for us all, but is required for us to prosper in the New Ecosystem. We must find ways to integrate our intelligently designed gardens into the larger open ecosystems. Climate change is upon us, and we must respond.

I’d like to close with some optimism. As I said, the NAP site gets 1.25 million visitors per month, which is an ocean of attention. Most of those visitors are people who would never have found our material without our open approach. A large proportion are likely to be grazers—people with only marginal interest in a topic, but who may become interested because they can read about it, online, for free.

The scholarly communications system has entered the climate change era. The “participatory culture” of the Web is changing the way intellectual material is integrated into a network of ideas. Centralization of both physical and virtual resources matters less and less—even for the fee-based content, which I fear will be left out of the Web-connected world more and more, since locked-away content can’t participate, even passively.

If we as humans are to weather the sociopolitical crises of the very real ecosystem trauma of the very real atmospheric climate change, as well as weather the diseases of zealotry, small-mindedness, and fear, we will need an educated, informed populace, whether officially “scholarly” or not. We need a nation of educated dilettantes, as well as specialists and scholars. We need a world where qualified, valid information acquires the “compound interest” of linking and confirmation from trusted sources—like librarians and publishers. We have the resources, the drive, and the skills to help make the information ecosystem better able to inform the larger world.

We have the capacity to help influence the developing information ecosystem—by feeding it constant quality, engaging in the new participatory culture, and thereby helping this new jungle grow not only thickly, but also well.

In the New Scholarly Ecosystem, we can continue to remain vital. But we must take risks to take advantage of this New Ecosystem’s possibilities. We can. It won’t be easy, but then again, neither was what we’ve been doing for the last century.

Thanks for your attention, and I look forward to further discussions in the years ahead.