Lost in the Park: Roy Rosenzweig’s Public History Legacy

I first learned of Seneca Village in 2020. That summer, people tired of having to explain why Black Lives Matter and with an online audience freshly enraged at racism turned to history to popularize further examples of how Black people in the United States had been systematically dispossessed and disempowered by the forces of White power. At the time I was researching Black park use in Kansas City, Missouri where Troost Boulevard, and later Highway 71, were used to displace Black “slums,” leaving lasting economic and health disparities.[1] I was finding, like other historians before me, that “although not created as a racial barrier, the parks and boulevards system served as one.”[2] The news of a Black village buried under what is now Central Park was not surprising. The renewed popular interest in Seneca Village prompted the Central Park Conservancy to install several historical markers at the site.[3] They formed a large outdoor exhibit near the existing New York Parks & Recreation marker.[4] What I did not know at the time was that this was not the first time Seneca Village became popular.

Started in 1825, Seneca Village, also known as Yorkville, was one of several permanent settlements removed during the construction of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s Central Park. The successful village with a population around three hundred, primarily composed of Black families, along with a few Irish and German immigrant families was struck from the map in 1856 and 1857 in an “unprecedented” use of New York’s eminent domain.[5] In all, around 1,600 people were removed from the land that would become the most iconic park in the world.[6] This is not a shocking fact. In both the future West Terrace and Penn Valley Parks in 1890s Kansas City, for example, park planners evicted predominantly Black and Irish people from several hundred homes in the West Bluffs and Vinegar Gulch.[7] Similar patterns of removal and greening occurred nationwide. What is surprising, and what captured the attention of the world in the early 1990s, is that the residents of Seneca Village were not squatters but landowners. They built three churches and even a school. They built homes up to three stories. This was not a transient group but rather an established community. Despite that reality, the planners of Central Park cast Seneca Village and the rest of the Central Park “squatters” as degenerates worthy of removal.

Figure 1: Egbert Viele, “Map of the lands included in the Central Park, from a topographical survey, June 17th, 1856; [Also:] Plan for the improvement of the Central Park, adopted by the Commissioners, June 3rd, 1856,” Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6850fc74-5e61-8806-e040-e00a18067a2c. The above map is a topographical survey of what existed in the park land before construction. The below map is a proposed map for the new Central Park. What was then Seneca Village can be seen in the above map on the top right corner of the Reservoir

Figure 2: Detail of Seneca Village from above Viele map.

After they “experienced the end of their world in stages,” Seneca Village was not entirely forgotten.[8] In 1871, laborers digging up trees at 85th Street and Eighth Avenue came across the coffins of the Irish girl, Margaret McIntay, and an unidentified “negro, decomposed beyond recognition.”[9] Later, in 1959, a gardener named Gilhooley found an entire cemetery.[10] Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, references to Seneca Village and Yorkville appear in the local press.[11] Seneca Village crops up a few times also in scholarship, usually as a brief reference.[12] Aside from Peter Salwen, who, in the late 1970s, began asking “how degenerate was it, really?” and expressing a wish that “perhaps some future Ph.D. candidate will dig deep enough (in the earth or in the archives) to tell us more,” none of these writers suggest that Seneca Village is “obscure.”[13] The fact that it is mentioned without many references or explanation indicates that Seneca Village may have remained quiet local knowledge.

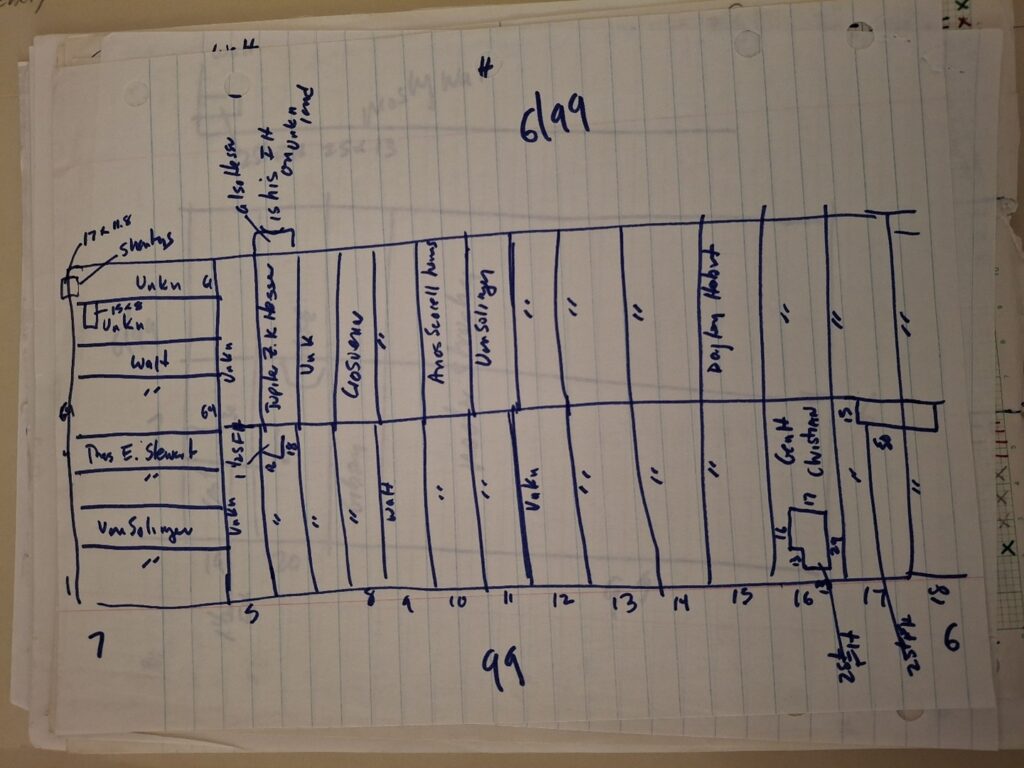

As Salwen wrote those words, Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar were answering his call. As early as 1987, Rosenzweig had produced a list of 323 residents in the village. They were a mix of laborers, shop owners, and farmers. The information he collated included their full name, number of family members, ID number, age, years lived in the city, employment, birthplace, and the number of lots, shanties, framehouses, stables, sheds, and piggeries they owned. Most of the sources he pulled these names from were baptismal records.[14] He also drew rudimentary plot maps of the village. In their 1992 book, The Park and the People, Rosenzweig and Blackmar included around thirty pages on Seneca Village, using it as the example of removal via eminent domain in creating Central Park.

Figure 3: Seneca Village, box 63, folder 1, Roy Rosenzweig papers, Fenwick Library Special Collections.

The publication of their work sparked a fire. Archaeologists began using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to investigate the site, confirming that evidence of the settlement remained. Excavations followed.[15] Nan Rothschild and Diana Wall led a large archaeological study, beginning by overlaying the 1856 Egbert Viele survey over the existing structures of Central Park. Rosenzweig sent his notes to the New-York Historical Society, which produced the renowned 1997 exhibit, “Before Central Park: The Life and Death of Seneca Village, an Exhibition at the New-York Historical Society,” and a number of educational programs.[16] Since 1992, countless historians have cited The Park and the People, expanding on its coverage of Seneca Village.[17] The local press covered each step eagerly.[18] Walking tours were and continue to be offered of the site.[19]

Figure 4: Seneca Village Exhibit, box 63, folder 3, Roy Rosenzweig papers, Fenwick Library Special Collections.

That interest has continued to today. Just this year, George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media awarded the American Historical Association’s Roy Rosenzweig Prize for Creativity in Digital History to the Envisioning Seneca Village project.[20] Roy Rosenzweig, who I came to know first as the author of the landmark works The Park and the People and Eight Hours for What We Will, is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in digital history. A social and labor historian and activist, his legacy is bringing history to the people who he championed. The prize, an award for innovation in digital historical work, is awarded annually to emerging projects. This year’s winner is an interactive 3D model with supplementary materials, which will soon feature a soundscape. RRCHNM Director Lincoln Mullen stated that Envisioning Seneca Village was selected as the prize winner because it “follows in Roy Rosenzweig’s footsteps not only in subject but also in its innovative use of new media to present history.”

Figure 5: Screenshot of the landing page for Envisioning Seneca Village’s 3D model.

Figure 6: Screenshot of Envisioning Seneca Village, Andrew Williams house. Williams was the first person to buy land in Seneca Village. He paid $125 for three plots of land.

Here at RRCHNM, our mission is to incorporate multiple voices, reach diverse audiences, and encourage popular participation in presenting and preserving the past. Roy Rosenzweig modeled that approach to scholarship in his own life. The Park and the People, and the flurry of subsequent scholarship helped to turn the public eye to history. Rosenzweig and Blackmar may not have discovered Seneca Village, but they brought it back to life. His legacy is apparent in articles, books, dissertations, historical markers, walking tours, social media posts, educational curricula, museum exhibitions, and, now, a fully explorable recreation of the site he helped make well-known. The enduring popularity and relevance of Seneca Village is a testament to the value of good scholarship and public history.

[1] James R. Shortridge, Kansas City and How It Grew, 1822—2011 (University Press of Kansas, 2012), 87.

[2] Robert Neil Cooper, “Kansas City, Missouri’s Municipal Impact on Housing Segregation,” Pittsburg State University Electronic Thesis Collection 86 (2016): 92, https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd/86 (quotation); Alexander Manevitz, “‘A Great Injustice’: Urban Capitalism and the Limits of Freedom in Nineteenth-Century New York City,” Journal of Urban History 48, no. 6 (2021): 7.

[3] Central Park Conservancy, “Discover Seneca Village” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=170981; Central Park Conservancy, “All Angels’ Church: Seneca Village Community,” https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171565; Central Park Conservancy, “The Wilson House: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171476; Central Park Conservancy, “Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171253; Central Park Conservancy, “Searching for Seneca Village,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171062; Central Park Conservancy, “African Union Church: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171414; Central Park Conservancy, “Gardens: Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=175885; Central Park Conservancy, “AME Zion Church: Seneca Village Community,” (2020: https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171330; Central Park Conservancy, “Reservoir Keepers: Seneca Village Community,” https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=173696; Central Park Conservancy, “Geology: Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=172965; Central Park Conservancy, “Livelihoods: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=172385; Central Park Conservancy, “Housing: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171895; Central Park Conservancy, “Irish Americans: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171612; Central Park Conservancy, “Summit Rock: Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171638; Central Park Conservancy, “Lanes, Lots and Streets: Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171734; Central Park Conservancy, “Tanner’s Spring: Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=172030; Central Park Conservancy, “Receiving Reservoir: Seneca Village Landscape,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=172111; Central Park Conservancy, “Andrew Williams: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=216962; Central Park Conservancy, “Downtown Connections: Seneca Village Community,” (2020): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=174287; Central Park Conservancy, “Guide to Seneca Village Outdoor Exhibit,” https://www.centralparknyc.org/activities/guides/discover-seneca-village.

[4] New York Parks & Recreation, “Seneca Village: Central Park,” (2013): https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=171184.

[5] Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Cornell University Press, 1992), 59.

[6] Nan A. Rothschild, Amanda Sutphin, H. Arthur Bankoff, Jessica Striebel Maclean, Buried Beneath the City: An Archaeological History of New York (Columbia University Press, 2022), 191.

[7] Shortridge, Kansas City and How it Grew, 63; Board of Park and Boulevard Commissioners, The Report of the Board of Park and Boulevard Commissioners: Resolution of October 12, 1893 (Hudson-Kimberley Publishing Company, 1893), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021237568&view=1up&seq=50; The Kansas City Star, July 25, 1896; Aug. 22, 1904; Nov. 1, 1919.

[8] Rosenzweig and Blackmar, Park and the People, 91.

[9] New York Herald, Aug. 11, 1871, 4, cited in Rosenzweig and Blackmar, Park and the People, 89.

[10] “Paddy’s Walk,” New Yorker, Jan. 10, 1959, 24, cited in Rosenzweig and Blackmar, Park and the People, 89.

[11] These include W.B. Van Ingen, “Landscape Illusions of Central Park,” New York Times, May 13, 1923; “Bright Outlook in the Yorkville Section,” New York Tribune, June 22, 1913; “Jolly Dunkers Turn Yorkville Back to a Farm: New York’s Original ‘Dips’ Meet to Have the Goldarndest Time! Fun at a Barn Dance, But the Old-Time Farmers of Jones’s Wood Didn’t Lose Their Goats, No, Sir!” The Evening World, Nov. 13, 1915.

[12] Edward Lubitz, “The Tenement Problem in New York City and the Movement for its Reform, 1856-1867,” (PhD dissertation, New York University, 1970), 381; Harry A. Williamson, “Folks in Old New York and Brooklyn,” 1953, box 96, folder 1, Literary and scholarly manuscripts collection, New York Public Library, described in Carla L. Peterson, Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (Yale University Press, 2011), 24-25; Kenneth Holcomb Dunshee, As You Pass By (Hastings House, 1952), 229.

[13] Peter Salwen, Upper West Side Story: A History and Guide (Abbeville, 1989), 46-47.

[14] Seneca Village, box 63, folder 2, Roy Rosenzweig papers, Fenwick Library Special Collections.

[15] Rothschild, Sutphin, Bankoff, Maclean, Buried Beneath the City.

[16] Seneca Village Exhibit, box 63, folder 3, Roy Rosenzweig papers, Fenwick Library Special Collections; “Teaching Black History with the New York Times School Program,” New York Times, Feb., 2, 1997.

[17] Leslie Maria Harris, “Creating the African American Working Class: Black and White Workers, Abolitionists and Reformers in New York City, 1785-1863,” (PhD dissertation, Stanford University, 1995); Patricia J. Ferreira, “Reading, Speaking and Writing Liberation: African-American and Irish Discourse,” (PhD dissertation, McGill University, 1997); Edward Eigen, “Birds, Dogs, and Humankind in Olmsted’s ‘Bramble’: A Story of Central Park,” An International Quarterly 42, no. 1 (2022): 3-21; Manevitz, “‘A Great Injustice’”; Sara Cedar Miller, Before Central Park (Columbia University Press, 2022); Diana diZerega Wall, Nan A. Rothschild, Cynthia Copeland, “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City,” Historical Archaeology 42, no. 1 (2008): 97-107; Alexander Manevitz, “The Rise and Fall of Seneca Village: Race and Space on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century New York City,” (PhD dissertation, New York University, 2016); Leslie M. Alexander, African or American?: Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861 (University of Illinois Press, 2008); Leslie M. Alexander and Ángel David Nieves, We Shall Independent Be: African American Place Making and the Struggle to Claim Space in the United States (University Press of Colorado, 2008); David Morris Brown, “The Wiping Out of Seneca Village,” in Ten Thousand Central Parks: A Climate Change Parable (Fordham University Press, 2025); Craig Steven Wilder, In The Company of Black Men: The African Influence on African American Culture in New York City (New York University Press, 2001).

[18] Douglas Martin, “A Village Dies, A Park is Born: Village Died When a Park Was Born,” New York Times, Jan. 31, 1997; Douglas Martin, “Before Park, Black Village: Students Look Into a Community’s History A Black Village That Gave Way to Central Park,” New York Times, April 7, 1995; Clyde Haberman, “The History Central Park Almost Buried,” New York Times, Feb. 28, 1997; “Reconstructing Central Park’s Black History,” New York Times, Feb. 22, 1998; “Stepping Back in Time,” New York Times, Jan. 31, 1997; “At the Site of Seneca, An African-American Fete,” New York Times, May 18, 1997.

[19] “Walking Tours,” New York Times, Feb. 20, 1998.

[20] Gergely Baics, Meredith B. Linn, Leah Meisterlin, and Myles Zhang. 2024. Envisioning Seneca Village. Website with interactive 3D model. envisioningsenecavillage.github.io.