World History Commons Adds Several New Primary Sources

World History Commons recently prioritized adding primary sources from lesser-covered regions and time periods to give a more thorough overview of world history for educators to pull from. As the Project Associate heading this endeavor, I focused my efforts on ancient and post-classical Oceania, North/Central America, South America, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

My largest effort went to include sources for Oceania, which had the lowest overall coverage of any region. Oceania, as a small region of dispersed island nations with less written history than other areas of the world, often receives less attention in curricula seeking to cover large amounts of space and time. However, Oceania’s vibrant history and culture can easily be incorporated into larger classroom topics regarding human migration and peopling, archaeology and material culture, early architectural advancements, imperialism, and colonization history. I included visual materials about pottery and figurines, canoes, maps, and stone structures.

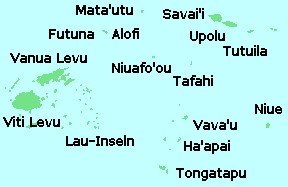

I added a Map of the Tu’i Tonga Empire, a maritime chiefdom from the island of Tonga powerful from the 13th-16th centuries CE. The value I find in this map is that it provides a visual aid for students of the island nations prominent in Oceania, so students can have a better idea of the geography of the nation and the connections between islands. This map also underscores that the region had its imperial powerhouses capable of territorial expansion before any sort of European colonization.

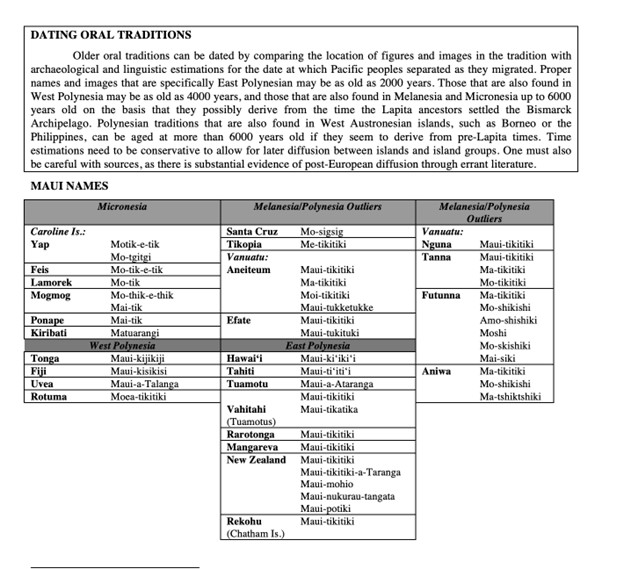

However, I found the Polynesian Oral Traditions source to be the most beneficial addition to WHC. Polynesian Oral Traditions is a compilation of creation myths, stories about the gods, cultural heroes, and other traditions from across the numerous island cultures, created by scholar Rawiri Taonui. Along with the legends and traditional stories, the author includes historical and cultural context regarding syncretism from the introduction of Christianity to the region, as well as information about the migration of people to the previously uninhabited islands. Oral traditions are essential to document, though it can be challenging to reflect both the breadth and the evolving nature of stories and myths. Here, Tanoui is able to analyze the traditions of numerous island cultures, but also give credence to the fact that some of these traditions date back as many as 6,000 years, giving a strong lineage to the stories and to the peopling of the islands. Further, I also thought this source would be a great addition to broader lesson plans discussing creation myths and oral traditions from ancient societies across the world, and it could be helpful to include Polynesian traditions to compare and contrast more commonly discussed traditions such as Ancient Greek or Roman traditions.

One challenge I found while working on World History Commons was writing for a new audience. Though I have worked in classrooms, I have not worked on an education project or written for teachers before. Distilling a large resource into an annotation that teachers can quickly look over is a daunting exercise. I approached this by outlining the important facts and themes of the resource (time, place, importance), and thinking about how the sources could augment standard lessons about historical themes, such as topics about creation stories, military history and war, religion, or social history.

World History Commons has added twenty-six new primary sources and five new website reviews to its already extensive collection of over 1700 primary sources and over 250 website reviews. By pinpointing the focus on certain regions and time periods, I sought to include only sources that truly augmented what we already included on the website. As World History Commons reaches its endpoint of including more resources on the website, I found it paramount to make sure that the project has good coverage of topics and that new sources are of great use to K-12 educators.