Talking to the Dead: Spiritualists and Seances

During my time working on the American Religious Ecologies project I became focused on female ministers and other types of religious leadership that appear in the Census. This interest aligns well with my dissertation research, which focuses on female preachers in the nineteenth century and their bodily experiences, analyzing even earlier examples of successful female religious leadership.

One religion with a large amount of female representation in twentieth century leadership are the different denominations of Spiritualists. In studying the National Spiritual Alliance, I found that almost 40% of the preachers listed on census schedules were definitely women, compared to the 25% of men listed, seen here in the map “Male and Female Pastors in the National Spiritual Alliance” (a number of pastors only had their initials given, making it hard to know their gender). Though the importance of female leadership and representation are one of the more significant markers of the Spiritualist faith, another important facet of their faith is the belief in communicating with the dead.

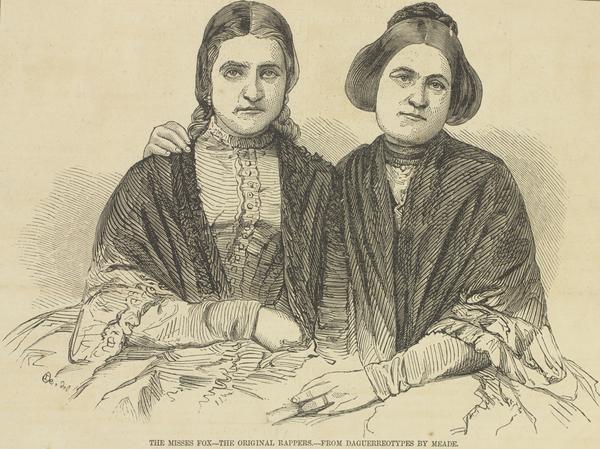

The larger Spiritualist movement began in 1848 with two young women, Katherine and Margaret Fox, began hearing ‘spirit-rapping’ in their house. Located in Rochester, New York, part of the burned-over district of the Second Great Awakening, the Fox sisters quickly gained prominence – and controversy – for the public seances they held as they toured across the state. They gained ardent followers who fully believed in their ability to communicate with the dead, while others believed them to be frauds fabricating the communication, or worse, communicating with demons. Nonetheless, the interest and belief in communicating with the dead continued, and Spiritualism became one of the fastest growing religious movements in the antebellum United States.

Early Spiritualist leaders were mediums who connected with the spirits of the dead and performed seances, sometimes in large, public venues, as trance speakers. Mediumship gave women largely accepted access to religious leadership, as many saw the ability to communicate with the dead as a feminine trait. Even as the popularity of Spiritualist seances declined after the Civil War, faithful followers formalized their practices and created branching denominations. The central tenant remained belief in communication with the dead, even as anti-Spiritualists continued to doubt the authenticity of those holding seances.